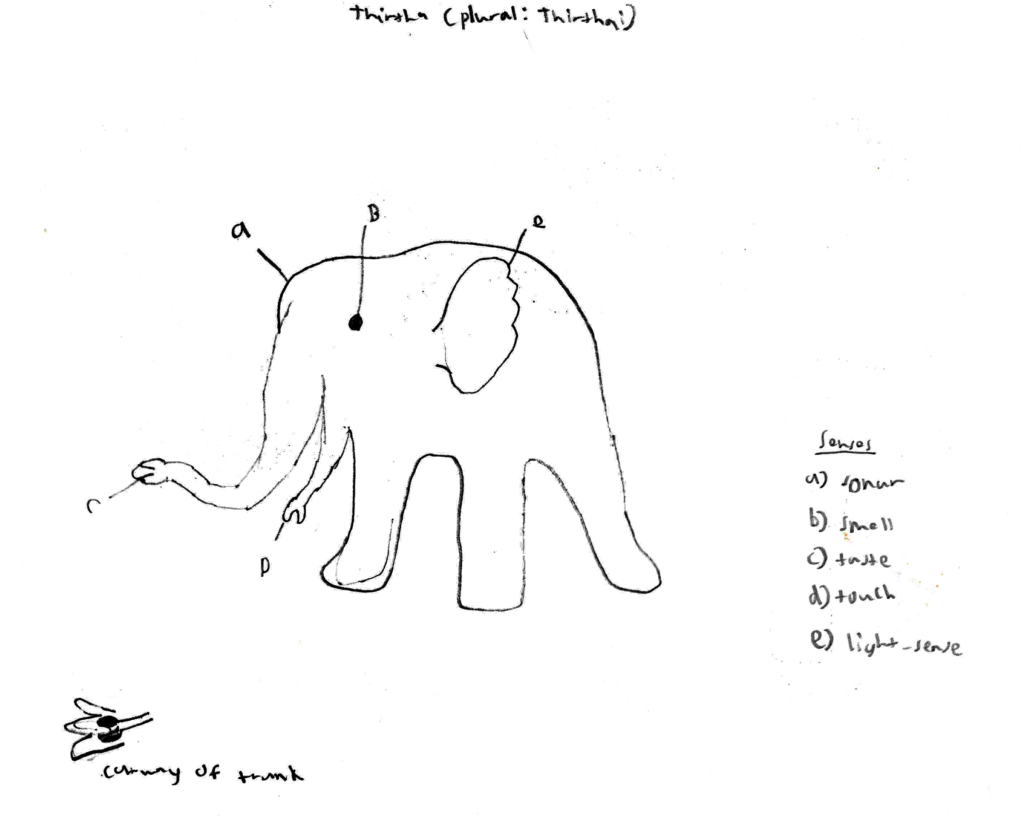

At first glance, Thirthai have been noted to resemble an elephant’s head combined with a squid. The second description is somewhat more apt, since Thirthai are descended from aquatic lifeforms that resembled cephalopods. Their evolution into their new environment has been driven by their native sun leaving main sequence, and the resulting drying of the oceans. The first terrestrial ancestors of Thirthai appeared 14 MYA.

Many of the quirks of Thirthai anatomy can be explained by their rapid terrestrial adaptation. Their internal skeleton is rudimentary, consisting entirely of a cage-shaped structure that protects the vital organs, as well as ‘vertebral’ columns that support the legs. For millions of years prior to their sun’s expansion, Thirthai had been deep-sea organisms, hence their reliance on sonar rather than sight. A Thirtha’s ‘eyes’ are light-sensitive flaps, that can only distinguish between light and dark.

Thirtha have multiple adaptations to their drying homeworld. Their bodies are covered by a layer of dead skin up to an inch thick, protecting them from skin cancer. A Thirtha’s lungs rival a bird’s in complexity, and their orange blood is highly efficient at oxygen transfer. Due to the extreme heat of their native environment, Thirthai are cold-blooded, unlike most sapiens. They can drink water as saline as 50 000 ppm; indeed, water less saline than 19 000 ppm can cause sickness or even death from osmotic shock.

Behaviourally, Thirthai are almost nothing like the elephants they resemble, being solitary carnivores. The average Thirtha is most comfortable alone, perceiving most other beings with suspicion and distrust. They evolved a limited capacity for social cooperation around 18 000 years ago, in order to survive the drying of their homeworld. Outside of extraordinary circumstances, Thirthai still lead solitary lives today, with their position within the Commonwealth being a matter of perennial debate.